EA new process can remove sand and dust from solar modules without using water. The method could have particular application in desert areas, where some of the largest solar arrays in the world are located. In the past, large truckloads of water often had to be brought to the sites for cleaning. The method developed by Sreedath Panat and Kripa Varanasi from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, on the other hand, uses electrostatic forces of attraction.

“Despite all the recent improvements in photovoltaic technology, dust accumulation on the surfaces of solar modules blocks a significant portion of the incoming sunlight and remains a major operational challenge for the industry,” the authors write in the journal Science Advances“. Just five milligrams of dust per square centimeter reduces power generation by 50 percent, as experimental measurements by Panat and Varanasi have shown. Such an amount of dust can accumulate in two months, and much faster in desert areas, for example due to sandstorms.

Dry cleaning solutions with brushes often left scratches on the surface of the solar panels that deflected the incoming light, the scientists write. And the amount of water that is currently used for the wet cleaning of such modules could be enough to supply two million people.

The MIT researchers therefore looked for another solution and found it in the electrostatic charging of the dust particles. Although an electrostatic process already exists for the solar modules of Mars rovers, the authors emphasize that it is very sensitive to moisture and can therefore hardly be used on Earth.

Panat and Varanasi first tested how mineral dust responds to electric fields. A large component of the dust – up to 75 percent – is silicon dioxide, which attracts moisture. The researchers conducted experiments at humidity levels of 5 to 95 percent.

The air is only humid enough early in the morning

The result: “As long as the humidity is greater than 30 percent, almost all particles can be removed from the surface, but it becomes more difficult as the humidity decreases,” Panat is quoted as saying in an MIT release. Nevertheless, the process even works in deserts that are very dry during the day. Because the humidity there regularly rises to values of more than 30 percent in the early morning when dew forms.

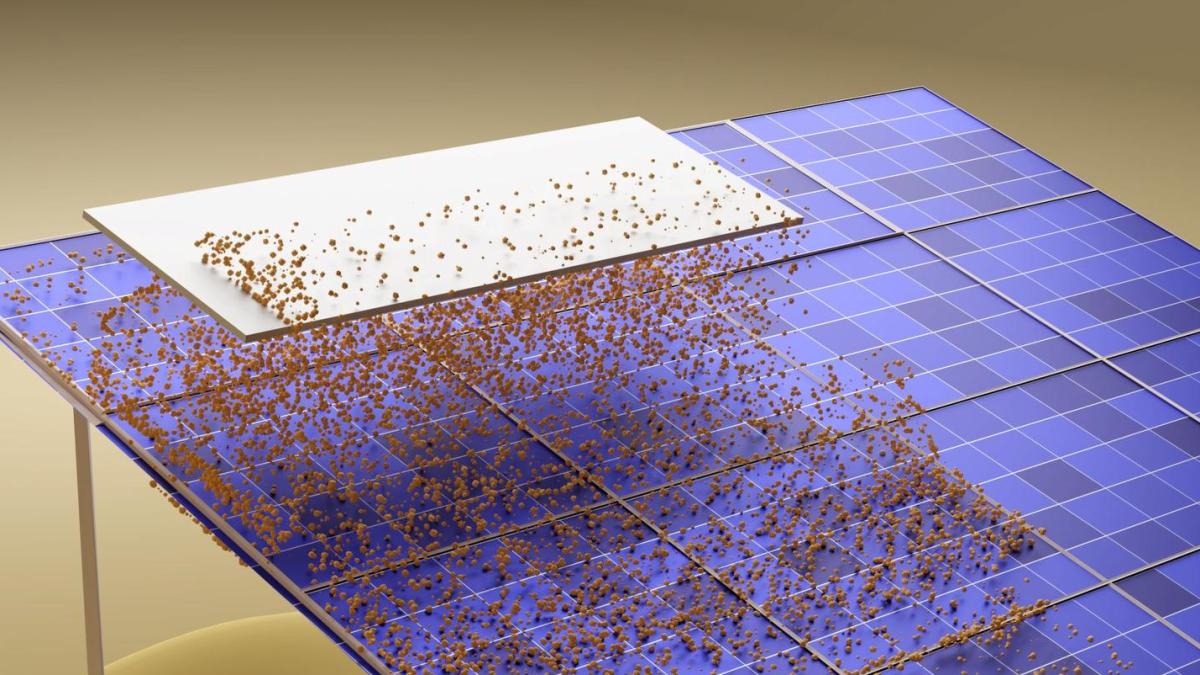

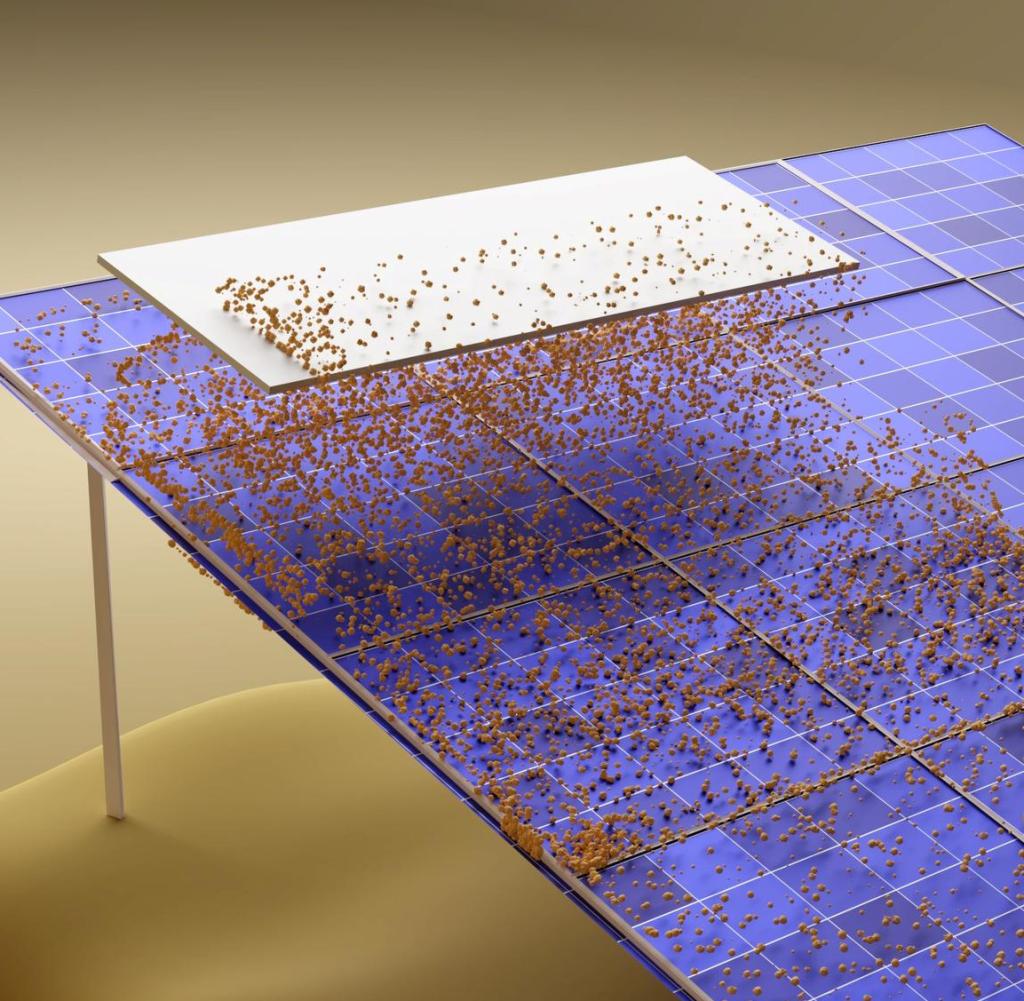

Building on this, the research duo developed a laboratory prototype based on the following process: The solar modules are given a large, transparent electrode with a thickness of five nanometers (millionths of a millimeter). When a voltage of twelve kilovolts is applied, this electrode positively charges the dust on the solar module. A movable aluminum electrode is then moved over the solar module at a distance of 10 to 15 centimetres.

Because it is negatively charged, it attracts the positively charged dust particles and thus removes them from the module surface. In solar systems, such an electrode could clean around 20 neighboring solar modules, the researchers explain. However, the prerequisite is a relative humidity of 30 percent or more.

“Although the applied voltage is on the order of kilovolts, there is no current flow between the top and bottom electrodes and therefore no power consumption,” the authors write. A little electricity is only needed to move and control the electrode. The method therefore works well for particles larger than 0.03 millimeters. According to laboratory measurements, 95 percent of the power of a solar module reduced by the dust can be recovered.